Conserving Coal History in a Bottle Pride and the United Mine Workers The Next Generations The Legacy of Coal

Timber Clay Farming Coal is widespread in Southeast Ohio. Mined and unmined, the history of coal is vast. Before humans began the coal industry that was integral in settling the coal towns that defined the region for generations, glaciers roamed. As they moved south, carving the farmland of Ohio, they collected sediment and eventually deposited it in Southeast Ohio. The Appalachian foothills were created, along with the coal that made the industrial revolution possible.

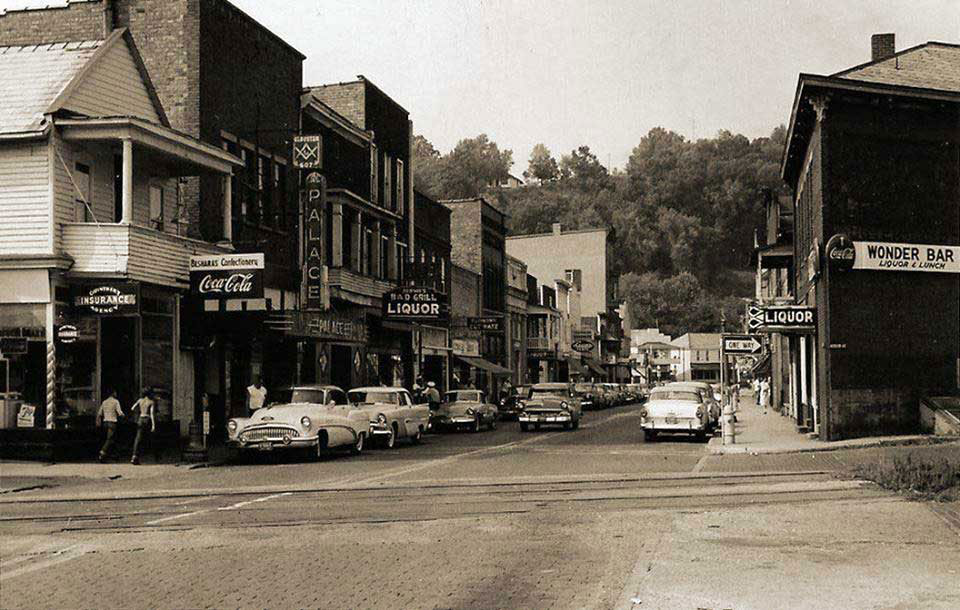

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Perry County, the number one producer of coal in Ohio in the late 1870s and early 1880s, according to Chris Wilson. Wilson, a native of Shawnee, Ohio, currently works alongside Sherryl Blosser at the Little Cities of Black Diamonds council (LCBD), a non-profit formed in 1990 dedicated to teaching and preserving knowledge about the former mining towns in Southeast Ohio.

After centuries of exploitation, people in former coal towns are reclaiming their history

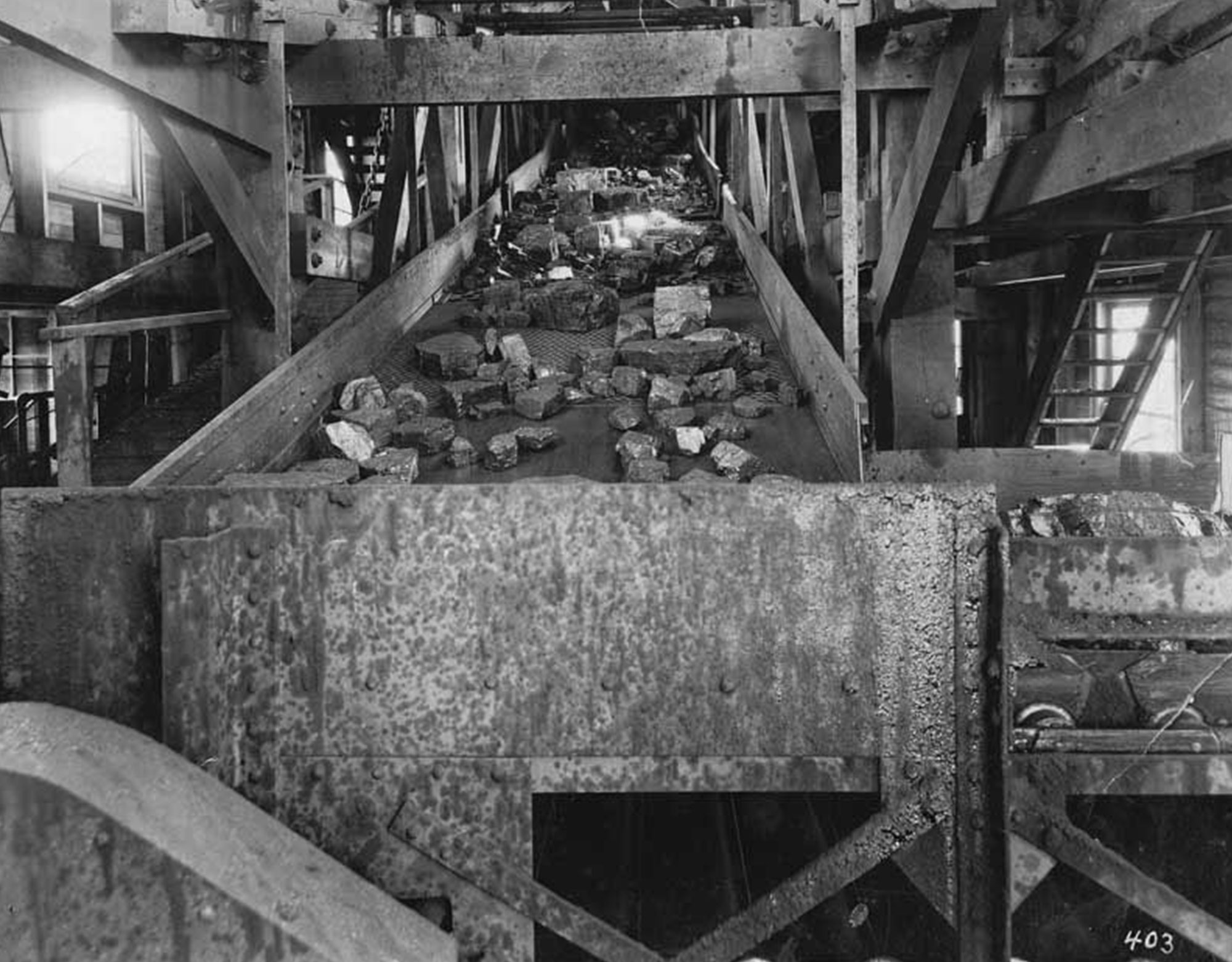

Mining began small scale and personal. Miners during the first few years of the 19th century had only small-scale mines. Digging out what they could from their own personal mines and taking only what they needed to sustain themselves and the immediate community.

Mining towns began forming after the American Civil War with the rise of railroads. Union Colonel James Taylor, who LCBD credits with discovering the coal fields in Perry County, took advantage of the developing railroad industry and began opening mines to ship and sell coal to companies in quickly developing cities like Chicago, Illinois.

Sherryl Blosser is a founding member of the LCBD and has been teaching and learning about the Little Cities for decades. She tells the story of a group of Hungarians that she stayed in touch with after touring the area where their ancestors first came to America.

She showed them cemeteries where they could look for their family name among the headstones. The group ended up translating head stones in Magyar, the dominant language in Hungary, for Sherryl Blosser. Sherryl Blosser also brought them to the old Hungarian church in the city Congo where they sang the Himnusz, the Hungarian national anthem.

Sherryl Blosser says that Hungarians and people from other countries came to the mines In Southeast Ohio for an escape.

“They were tired of monarchies and dictatorships. They wanted basic rights and democracy was on the move. If they could not get it going in the country you were staying in, they would go to America because they already had it.”

This was years ago now, according to Sherryl Blosser. The last time she saw any of them was about 10 years ago.

Sherryl Blosser’s son, Cam Blosser, has followed in his mother’s footsteps preserving the region's history, although his way of preserving the history is through glass bottles.

The bottles, most of which are from the creek behind the Blosser house, show the many nuances of life in the former mining town New Straitsville.

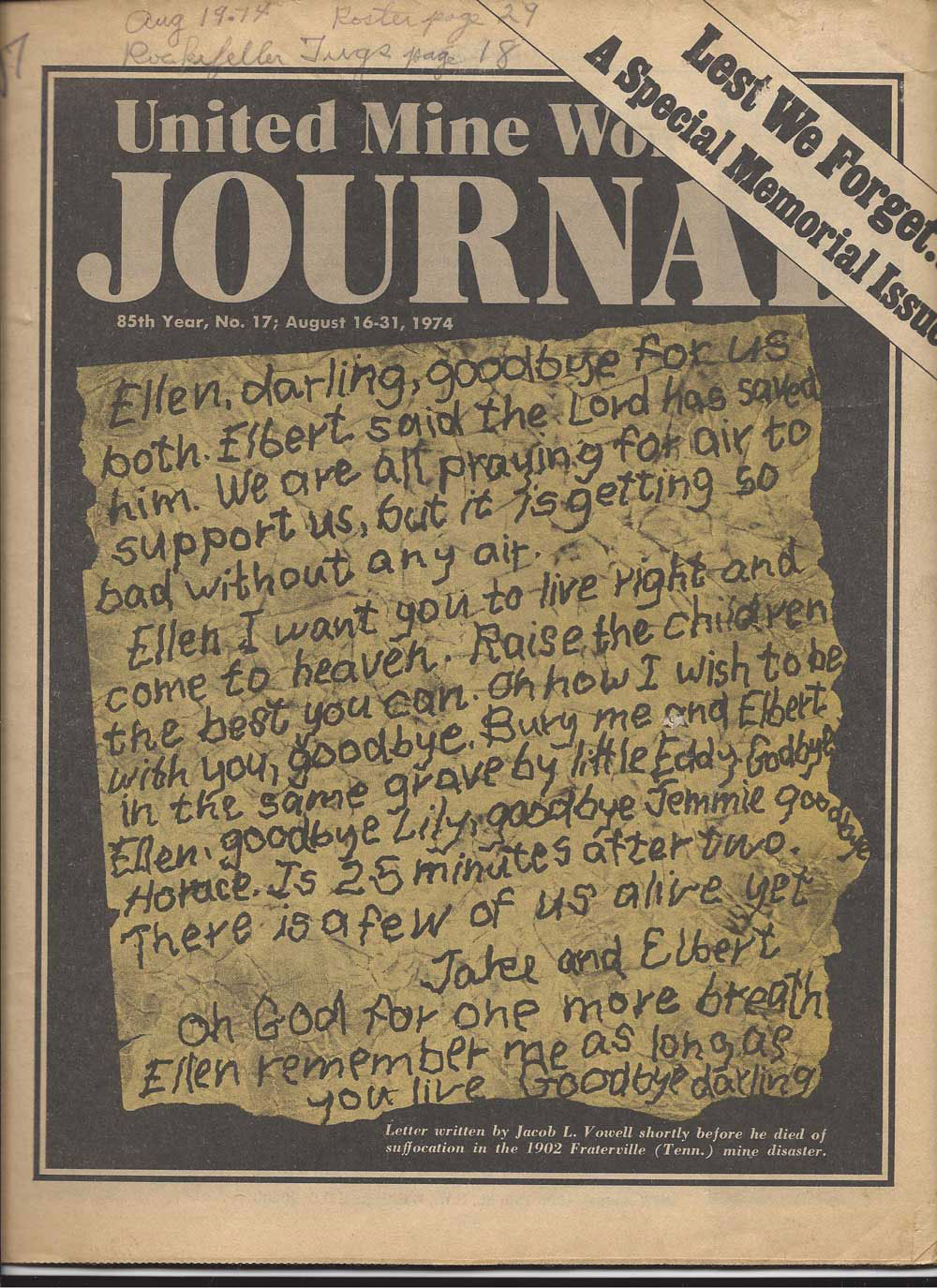

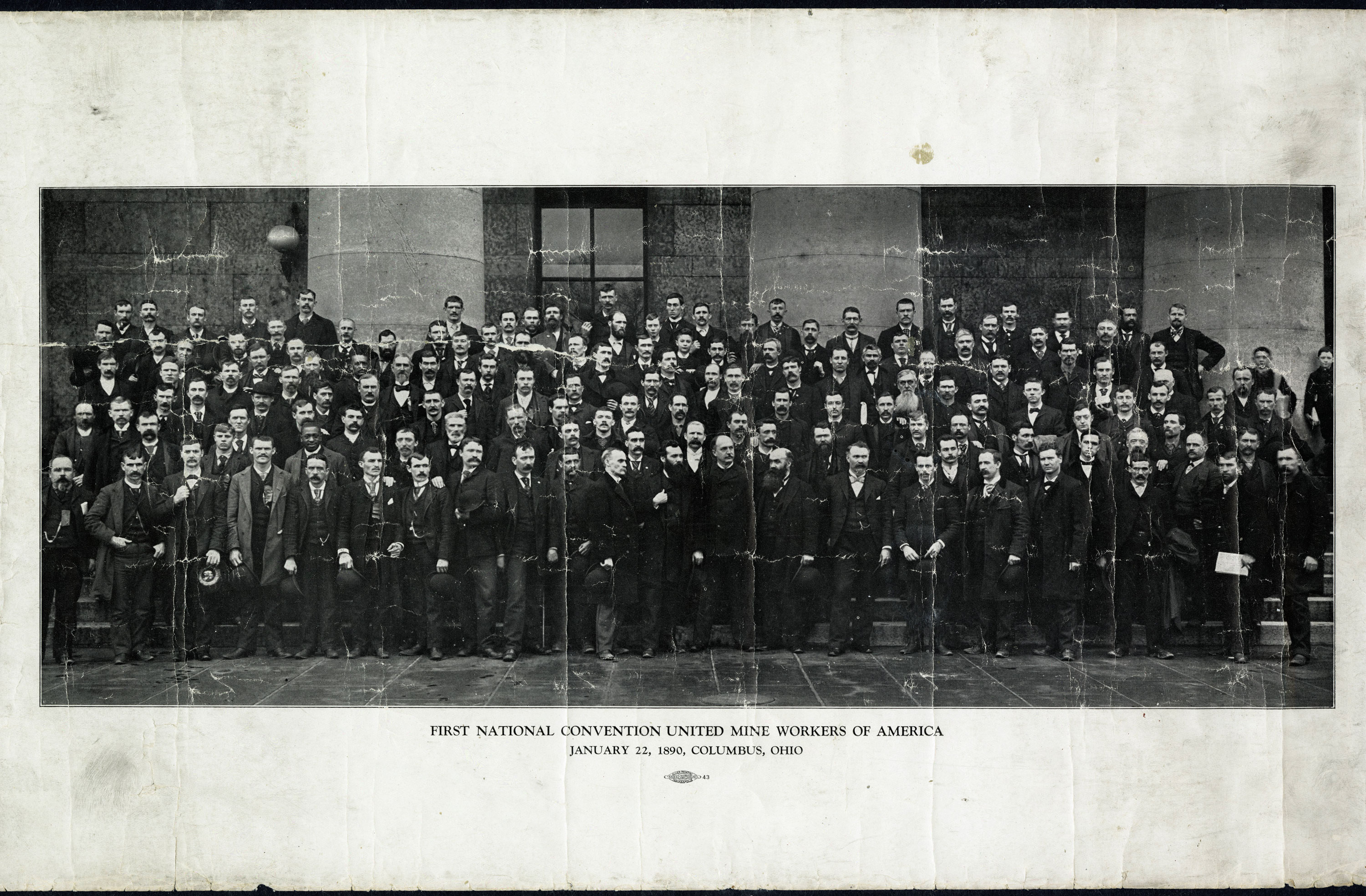

The creek where Cam finds most of his bottles passes Robinson’s Cave, the birthplace of the United Mine Workers (UMW). The UMW was formed when the National Progressive Union of Miners and Mine Laborers and the Knights of Labor joined to fight the harsh working conditions forced upon them by the same companies who delivered them from their previous oppressors. During the 1860s, miners met in the darkness of Robinson’s cave to discuss plans for improving the dastardly conditions.

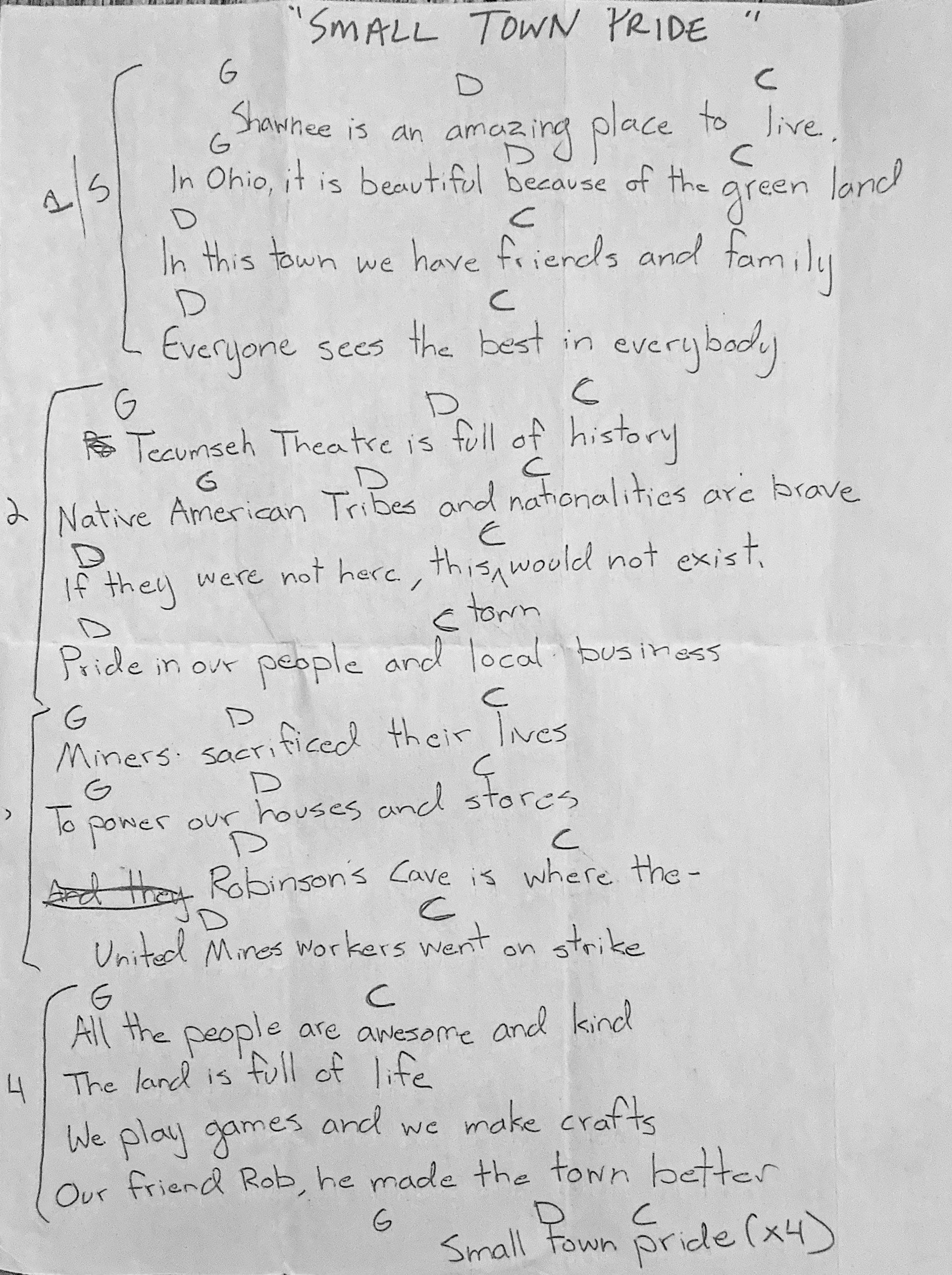

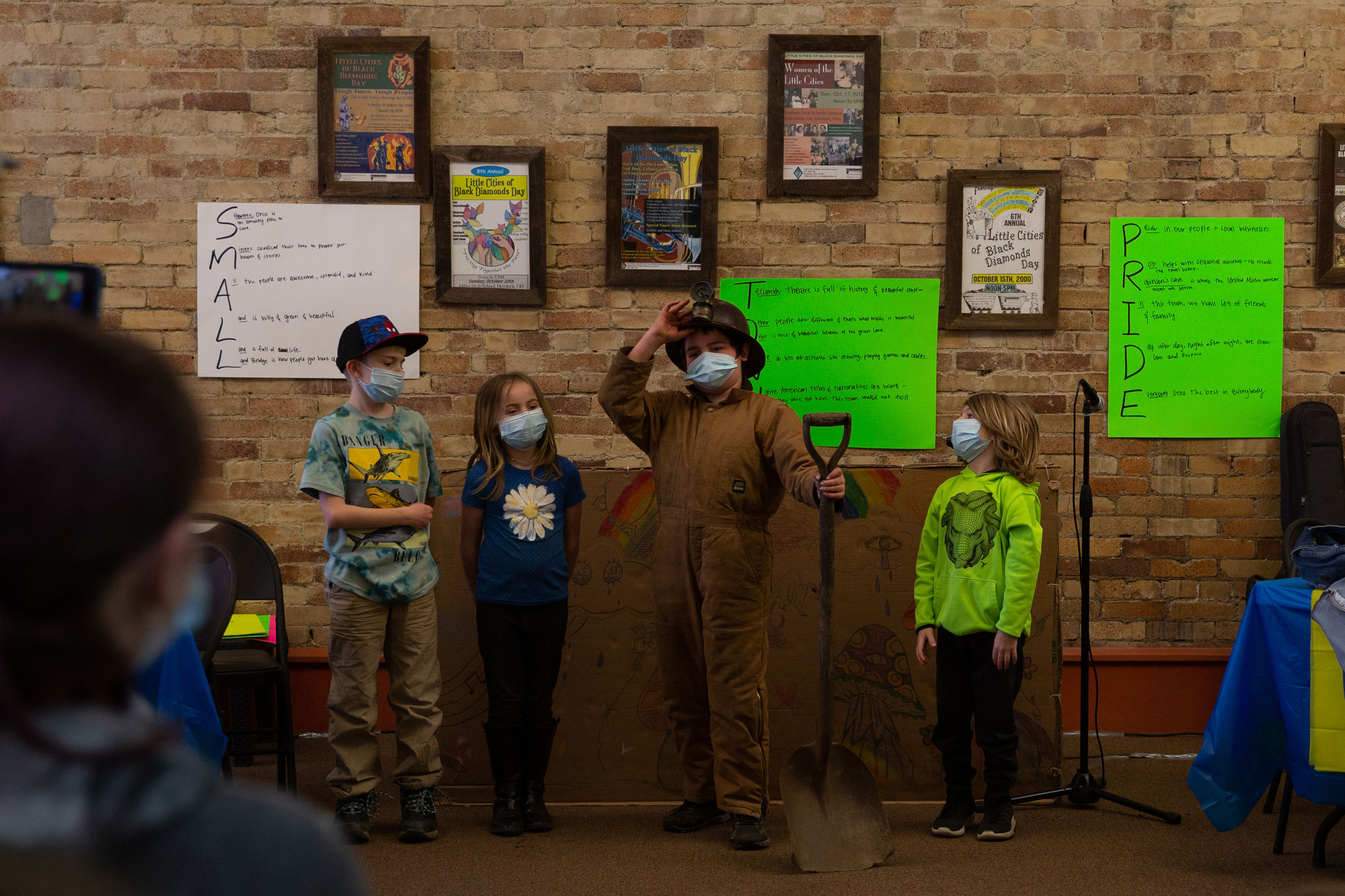

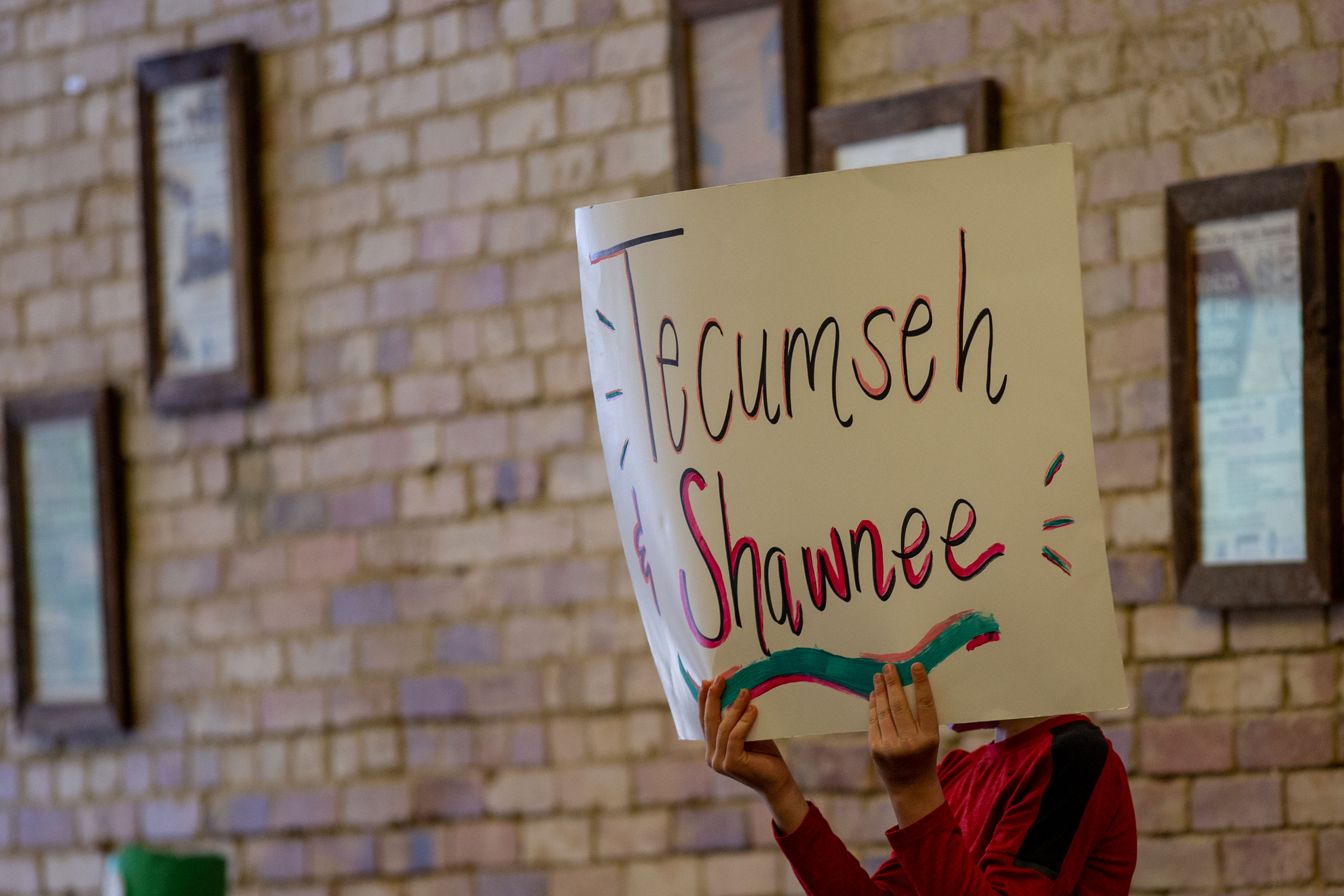

As Cam Blosser continues discovering history hidden in glass bottles, his mother continues telling stories of history at Saturday Matinees. Saturday Matinees is a six week long program this spring for children to learn about the history of the area. On Saturday, March 26 they held a puppet show for families to see what they learned. After the puppet show, the kids gathered in front of the cardboard stage to sing “Small Town Pride,” a song written by a local high schooler. The young children bashfully sang about what makes Ohio, and specifically Shawnee, unique.

Pride is a common thread through the Little Cities. People take ownership of the history of coal around Shawnee. Along with giving immigrants a chance to be free from dictators and monarchies, coal production in southeast Ohio paved the way for further industrial and westward expansion of the United States.

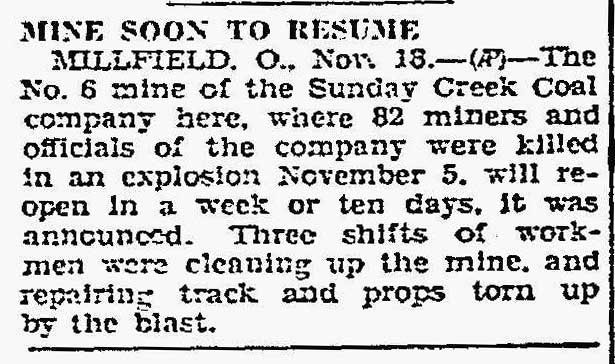

As the song mentions, miners found dignity in being able to power their homes directly from the earth, although many lost their lives doing so. The Millfield Mine Disaster, Ohio’s worst mining accident, occurred less than 20 miles away from Shawnee and the Tecumseh Theater. The disaster claimed 82 lives, and with the small population of the infant city of Millfield, it affected most families.

Mining towns formed after the American Civil War with the rise of railroads. One of the first people to take advantage of the railroads was Colonel James Taylor, who LCBD credits with discovering the coal fields in Perry County.

After serving in the Union Army during the civil war, Taylor turned to southeast Ohio and began buying land to open coal mines. After realizing the profit available in Perry, others began buying his mines and creating new ones. During the 1870s to the early 1900s, those mine owners advertised work in their mines taking shape as groups from Hungary, Scotland, Britain, Germany, and even formerly enslaved people from the southern states came to work in the mines.

Education of the history in Shawnee does not stop with elementary kids though, and it goes beyond puppet shows and songs. Since February 2021 there have been high schoolers from Miller High School interning at the Tecumseh Theatre in Shawnee.

Youtsey says that the pride of living in the cities built by the coal industry goes beyond the group of cities known as the Little Cities. Each city has unique history to be proud of, and high schoolers at Miller make sure their cities are well represented.

“It was a petty, in your face type thing,” Youtsey, who is from Shawnee, said as she mimics taunting a classmate. “We have this, you guys don’t have that. We were more included in history.”

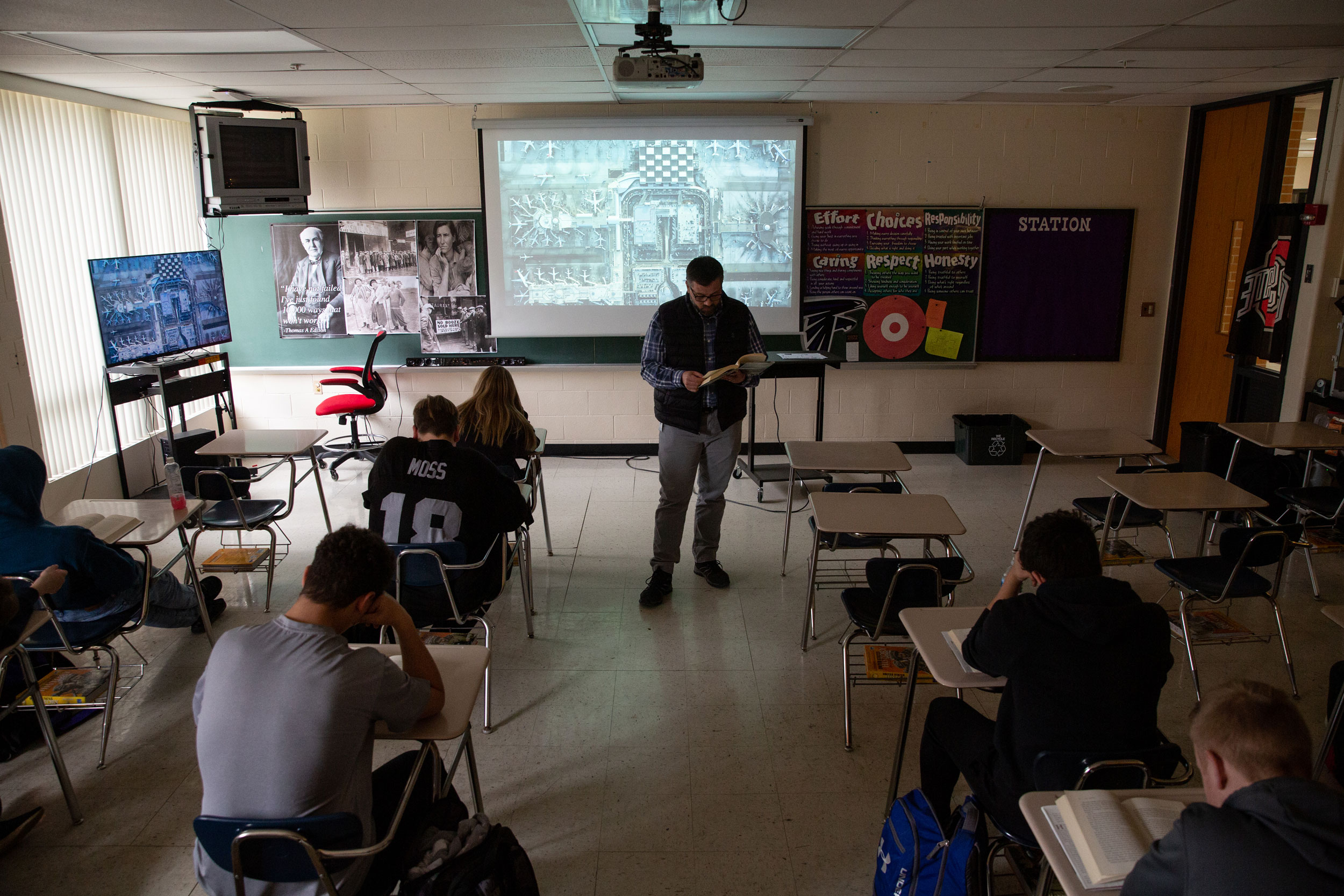

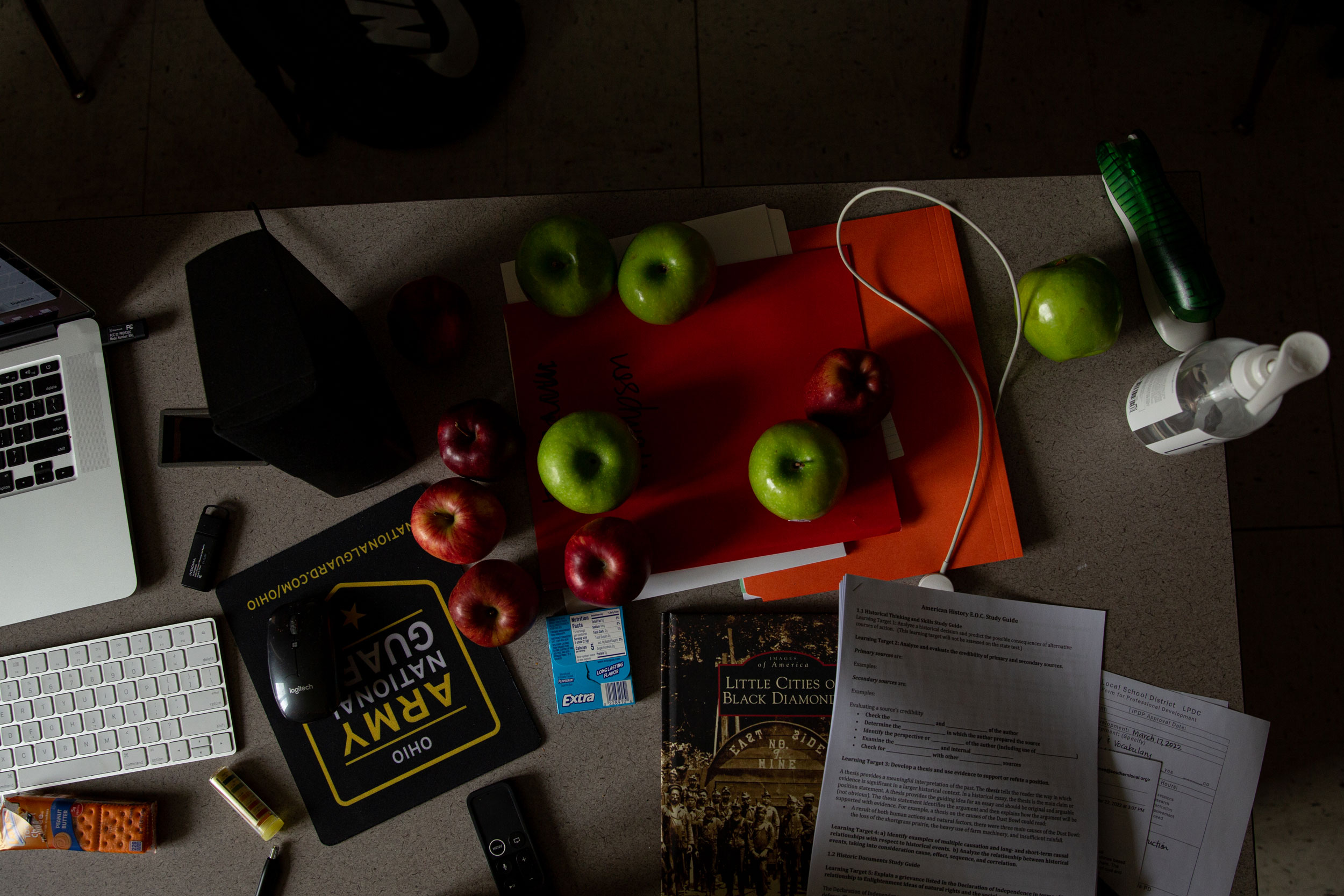

There have only been five students enrolled in the 40-hour internship since it began in spring 2021, but there are more opportunities springing up through Miller High School for students to pursue knowledge about their own town’s history, as well as the history of the towns around them. Many of those towns land in Perry County, and that is how history teacher Jason Thompson came up with an idea for a new course, The History of Perry County.

Thompson has seen first-hand the pride that stems from being from each town, especially New Straitsville and Shawnee. He tries not to identify his students by where they are from though, saying that Miller is one community.

“The importance of local histories to me, is to help my students understand that they can achieve things. Not necessarily great for their own pride’s sake, but to understand that they can be and do great things,” Thompson said. “There is a rich history of immigration in this area with the backgrounds of people that came here to work specifically in the coal mine that never would have come here, if not for that. And they came, they built a life. They left a legacy.”

“I would imagine communities competed with each other and saw their community pride as something they wanted not to be second place,” Thompson said. “Since the 1960s, Miller High School has been the glue that holds the communities together.”

Most competition between towns was before World War One when each mine had one nationality of workers. They were pitted against each other by mine owners, which was not especially difficult because of the turmoil that already existed between many of the nationalities. Irish Catholics, for example, did not get along with protestants or Germans so they remained separate until it was dangerous to for Germans in America because of World War One, according to Sherryl Blosser. The tactic of separation was to keep mine workers from forming a stronger labor union, which failed and labor groups like UMW unified miners against their oppressors.

After World War Two, the mining industry turned from manpower to machine power. Just as the railroads had done nearly a century earlier, machines that could mine more coal faster took over the coal industry. Along with the new technology, companies also sought better sources of coal. Coal deposits in West Virginia were of better quality and abundantly available compared to the coal in Southeast Ohio and soon mining companies moved south. The industry not only left Southeast Ohioans jobless, but the industry left the land scarred.

Buckingham Coal Company was the last coal mine in Southeast Ohio. It was bought by Westmoreland Coal Company in 2019, and in less than two years the number of people working at the plant went from just over 200 to eight according to engineer Albert Seimer.

Seimer is still working at the plant, but it is not churning out the coal like normal. Instead, the few who have kept their jobs at the plant are in full reclamation mode.

Reclamation is the process of returning everything to the way it was before coal companies began mining there, Seimer says. There are lasting effects though, like acid mine drainage (AMD).

AMD occurs when water seeps into a mine and brings heavy metals like iron into larger bodies of water like creeks. The interaction between metals and oxygen turns the water orange and poisonous to drink. Organizations like Rural Action have been treating acid mine drainage in many ways, so water quality in former mining towns has steadily improved. Since partnering with John Sabraw, an artist and professor at Ohio University who has been developing pigments to use in paint from the AMD, newspapers and magazines across the United States have been covering the efforts to fight AMD in Southeast Ohio, but poisonous water is not the legacy of coal.

Growing up in Appalachia and teaching Perry County’s history, Thompson has experienced being proud of history in the area while looking for new ways to grow, and teaching local history is Thompson’s new way to grow.

“The importance of local histories to me, is to help my students understand that they can achieve things. Not necessarily great for their own pride’s sake, but to understand that they can be and do great things,” Thompson said. “There is a rich history of immigration in this area with the backgrounds of people that came here to work specifically in the coal mine that never would have come here, if not for that. And they came, they built a life. They left a legacy.”

The legacy of the coal industry of Southeast Ohio is in the former mining towns. The people living, preserving, and teaching their history to the next generations are who make the coal industry’s legacy.